Antique Dutch Dolls

Antique dutch dolls hold different names among collectors. Grödnertals, pennywood Dolls, dutch dolls, and peg leg dolls stand among some of the most used terms. The term “dutch dolls” has led to much confusion as to their origins. So a bit of history around the 19th century English speakers’ use of the phrase “Dutch” and a little history of the term “grodnertal” is needed for better understanding.

Some may say “dutch” was an Anglicized or English speaker’s lazy way of mispronouncing “Deustche.” See below for more examples of where “Dutch” means “Deustche” in areas of America where the Germans settled.

The Daily Telegraph & Courier (London) on Thursday 18 October 1888 included an article where the reporter wrote that dolls of “long ago” were chiefly imported to England from the Netherlands. The reporter called them Dutch and German dolls with perfectly round heads, a little stuck out nose, black painted hair parted in the middle, with a stuck out thumb, pointed toes, jointed and articulated. The writer claimed they came from countries on the Rhine, France and Switzerland.

Jointed Wooden Dolls

In 1845 a George White advertises a new stock of wood jointed dolls for sale for the Christmas season (Alexandria Gazette. December 10, 1845. p1). One wonders from where White’s dolls originated.

One can study some early German specimens from a preserved toy-maker’s catalogued archived at Gallica here. The catalog dates from around 1830. In it you can see the resemblance similarities to the dolls now known as milliner’s dolls.

The Youth’s Companion of March 1879 (v. 52) shows an illustration on page 103 of a wood jointed doll described in a child’s story giving hints to a doll structure and profile familiar to the writer as well as the idea that it probably had a wig. A wood jointed doll with a rolling knee joint can be found for sale on page 378 of the Youth’s Companion v. 52 for October 30, 1879.

“Dutch Dolls” in 19th Century English Literature

The term “Dutch Dolls” appears in many pieces of 19th century English literature or publications. The term did not always refer to peg jointed wooden dolls but usually refers to German origins in English literature

Dutch Dolls and Noah’s Ark

George Daniel mentions dutch dolls and other toys in 1842 in his book, Merrie England in the Olden Time. In the sentence context Noah’s Ark and other wooden toys shine light on the typical German toys made during the time.

Charles James Lever in 1852 mentions dutch dolls in his book The Daltons or Three Roads in Life while narrating a scene of characters ascending up toward the Stuttgart castle of “Alten Schloss” in west Germany. In a conversation about prices of items or goods sold in the village, the character Haggerstone comments, “I am no connoisseur in Dutch dolls nor Noah’s arks,” making reference to well known and common German wooden made toys.

Dutch Dolls Not Made of Wood

Jerrold Douglas William in 1853 described a trade in Dutch dolls in Japan and then described dolls as having eyes that open and shut and mouths that could make sounds. This leads to an implication not necessarily a type of doll but the origin of the dolls.

This happens again in 1871 when Edmund Hodgson Yates describes “dutch dolls” in his book Dr. Wainwright’s Patient as having heads and chests made of shiny composition but bodies made of calico and sawdust.

Another example that refers to origin and not to the type of dolls occurs in 1877 Richard Blackmore describes dolls with heads, hands and feet made of wax as dutch dolls in his book The Maid of Sker.

1887 Sybil’s Dutch Dolls

Pennywood Dolls

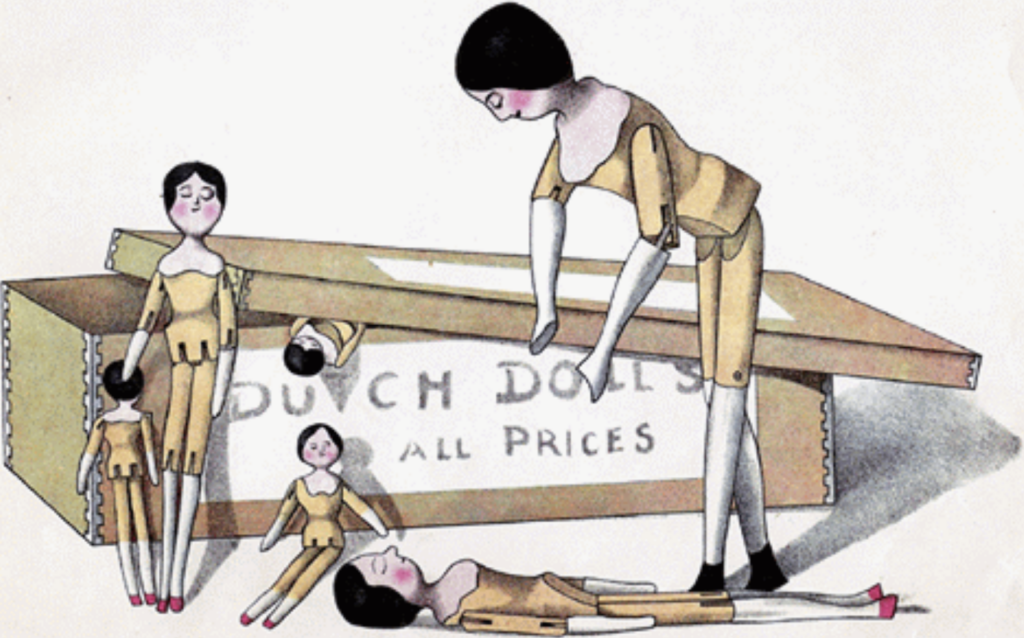

A book appeared in 1887 by F. S. Janet Burne called Sybil’s Dutch Dolls. On the cover dolls stand next to one another with a jointed wooden doll in the center. On the inside next to the cover page an illustration shows a girl in a toy shop with jointed wooden dolls hanging together on display. The first page of poetry shows a crowd of these dutch dolls holding a banner that reads, “Cheap dutch dolls for a penny.” This banner may have contributed to people calling them “penny dolls” or “pennywood dolls.”

1895 Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwog

In 1895 Florence Upton published a book, “Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwog.” Ads appeared with illustrations of the story giving us today ideas of the type of jointed wooden dolls the term “dutch doll” referred. The German publication Dekorative Kunst in 1902 used the term, “Penny-Holzpuppen,” which translates as “penny wooden dolls” (about the golliwog see here.)

The Anglicized German Word “Deutsch”

The Dutch Fork, SC

At first glance one might assume “Dutch” refers to the Netherlands. But one must take into account the term used by English speakers. For example, in the state of South Carolina in the USA there lies an area of called “The Dutch Fork” in Newbery County near the city of Columbia. In this area known as the Dutch Fork dwelt many German families that immigrated around 1755. The pronunciation of the German word for German for the English speaker would usually come out sounding more like “Dutch” and thus they called the area the “Dutch Fork.”

Pennsylvania Dutch

The same concept refers to German speakers who settled in Pennsylvania for they are known as the Pennsylvania Dutch.

Antique Dutch Dolls

Therefore we might conclude the term “dutch doll” referred to dolls from Germany or German speaking areas. The terms seems to have transformed over the years to refer more specifically to the antique jointed wooden dolls with the wooden heads.

Queen Victoria’s Dutch Dolls

In 1892 the Strand Magazine featured a story by Frances Low about Queen Victoria’s dolls making reference to them as dutch dolls while emphasizing they were NOT Dutch (meaning not from Holland). Photographs of her dolls show jointed wooden dolls whose round heads had painted black hair with curls around the faces and top knots. Later in the article Frances Low refers to one as a common twopenny Dutch doll.

In August of 1892 the French literary and political journal Le Gaulois wrote an article found on page 1 of the August 16 issue about the discovery of Queen Victoria’s dolls by Sir Henry Ponsomby. The writer explains clearly that it was undeniable that all the dolls were from Nurembourg. Therefore let it rest, that Queen Victoria’s dolls were not from Holland!

Grodnertals from Grödner-Thal (Val Gardena)

Many collectors sometimes refer to the antique dutch dolls with the carved heads and peg joints as “grodnertals.” The term refers to items made in the alpine valley of Grödner in the Tyrol mountains or the Grödner-Thal, known in English as the Val Gardena.

Alfred Dove wrote in 1872 about the wood work in the Grödner-Thal. He called it an alpine hideaway where the Val Gardena (Grödner-Thal) flows. According to Dove there worked the once world-famous population of woodcarvers making the once popular children’s toy, the articulated dolls, that traveled into the world. In those Dolomite mountains of the 19th century, people understood German, but rarely replied to it. He claimed their heart language was Italian. Knowing this, one might claim, the old wooden grodnertal dolls were “Italian” made (Im Neuen Reich. 1872).

1877 Description of Wood Carving in the Grödner-Thal

Ludwig von Hörmann wrote in 1877 about the wood carving trade in the Val Gardena or Grödner-Thal. In his book Tyrolean Ethnic Types, Hörmann explained that the people of the valley began focusing more and more on wood carving with the decline of the lace trade.

Hörmann wrote that at that time the area had about 2500-3000 carvers that worked mainly in the winter. The entire family worked at home usually for twelve hours a day with the exception of Sundays or holidays. The carver would have a sample hanging on the wall in front of him. Carving would include toys, animals, and articulated men. A family could produce 100 dozen dolls in 24 hours. A skilled craftsman could carve a figure 30-36 inches high in one day. Four-fifths of the items made went abroad to England, France, North American and to the East Indies.

However, according to Hörmann the coarser carved goods mentioned above rarely came from Val Gardena, Thale itself, but were manufactured in the neighboring valleys of Fassa and Gaderthal (Enneberg) and brought over to Val Gardena. This was only possible with great effort in winter as the people had to cross the avalanche-hazardous yoke with a load on their backs and a long mountain stick in their hand. (Again Hörmann explains the possible Italian origins of some of the adored antique grodnertal dolls. See the Museum Gheirdeina.)

The four great wood-carving districts in the seventeenth century were Oberammergau, Berchtesgaden, the Grödnertal, and the country around Sonneberg in Thuringen.

Stone Pine for Dutch Dolls

Both the finer and coarser pieces carved in the Val Gardena came from stone pine trees which grew in the highest regions of the mountains on public lands but had to be bought for large sums of money. So many cutters stole the wood. They estimated then that 2,000 logs were stolen every year.

Carvings were attempted from other compact types of wood, such as walnut, apple, maple, birch, burwood and redwood. Products of a finer type were made from it. Spruce and pine wood were used for the most common goods. Experiments were also made with beautiful alabaster, which was quarried in the Thale itself according to Hörmann.

Grödnertal Term in 1928

Philip Hereford used the term ‘grodnertal’ as an adjective in 1928 to refer to businesses in the Val Gardena when translating Karl Gröber’s book Children’s Toys of Bygone Days. In his book we see the mention of Oberammergau and costume dolls (making us wonder if his terms could refer to such dolls like those of Queen Victoria’s antique dutch dolls).

“A center of the toy trade unconnected in any way with Nuremberg, sprang up in the second half of the 18th century in South Tyrol, in the Grödnertal, with St. Ulrich as its chief town. At the turn of the nineteenth century there were already over three hundred wood-carvers in this district who disposed of their wares through their busy agents. But for a long time, as already said, they had to get their wares painted in Oberammergau, until, in fact they had themselves acquired the necessary experience. They made chiefly animals and costume dolls, or the once so popular and picturesque caricatures of cripples and beggars, objects which have less attraction for us to-day. Many of the Grödner wares were peddled from house to house in packs by itinerant vendors. We hear of some such who thus journeyed to places as far apart as Lisbon and Russia. The greater part of their productions was, however, disposed of abroad through the wholesale trade. In 1810 no less than 348 Grödnertal firms had depots in 130 different places abroad. There was at that time hardly a centre of trade of any importance where a merchant from this remote valley had not his depot, and the whole population of the valley hardly exceeded 3,500 people. It was only towards the close of the nineteenth century that this flourishing export trade dwindled, owing to the imposition of high customs duties in the countries of the principal markets. In addition to these three large districts of the toy industry there were, in Germany, other smaller centres, which, however, hardly came into consideration in the face of such important competitors, though we hear of old-established industries of the kind in the Viechtau, in the Black Forest, and in the Swabian Alps at Geislingen.”

(Karl Gröber. -English version by Philip Hereford- Children’s Toys of Bygone Days : a history of playthings of all peoples from prehistoric times to the XIXth century. 1928).

One begins to understand that Alpine Italian made wood jointed dolls came into Germany by people do commissions to have dolls exported abroad. Thus the English speaking people associated the dolls with Germany calling them “Deustche Dolls” and pronouncing it as “Dutch Dolls.”

One may be interested in the modern Dolfi dolls and Val Gardena today.

Queen Anne and Georgian Dolls

Earlier jointed wood dolls appearing during the time of King George IV of England may hold the descriptor of “Georgian dolls.” Evern earlier wood jointed dolls rare and very hard to find are known as “Queen Anne Dolls” and need need another post.

Further Reading

You may like to know more about:

- antique American jointed wooden dolls known as Schoenhut

- how to identify antique dolls