Sonneberg owes its fame in the toy industry to the abundance of wood supplied by the forests of Thuringia. In 1900 the German empire explained in the official exhibition catalogue at the International Exposition in Paris that any toys made within “5 hours” of Sonneberg were considered Sonneberg toys. The catalogue claimed the Sonneberg toy industry went back many hundreds of years. For the sake of this post, we will look at a history beginning the mid 19th century.

Some history of Sonneberg, a city of dollmakers appears in old American newspapers. These historical articles and stories reveal a perspective of the history of Sonneberg’s doll industry and its growing trade relations with the U.S.

- newspaper story from 1875 – Sonneberg, Home of the Dolls

- newspaper story from 1877 – US Tariffs in the History of Sonneberg

- newspaper story from 1886 – Sonneberg, Toiling Toymakers

- newspaper story from 1893 – Sonneberg, City of Dollmakers

- newspaper story from 1905 – Sonneberg, Santa Claus’ Doll Factory

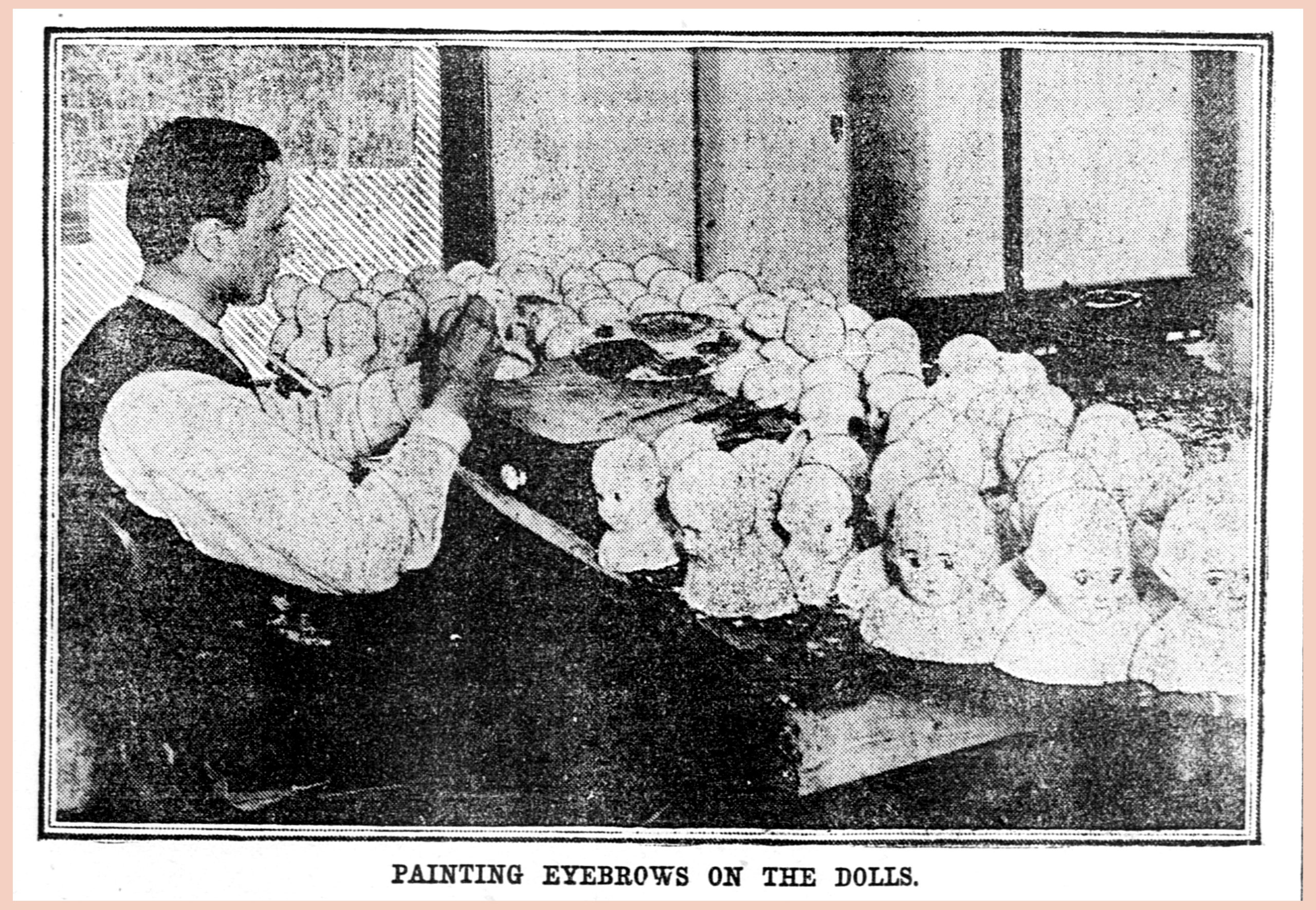

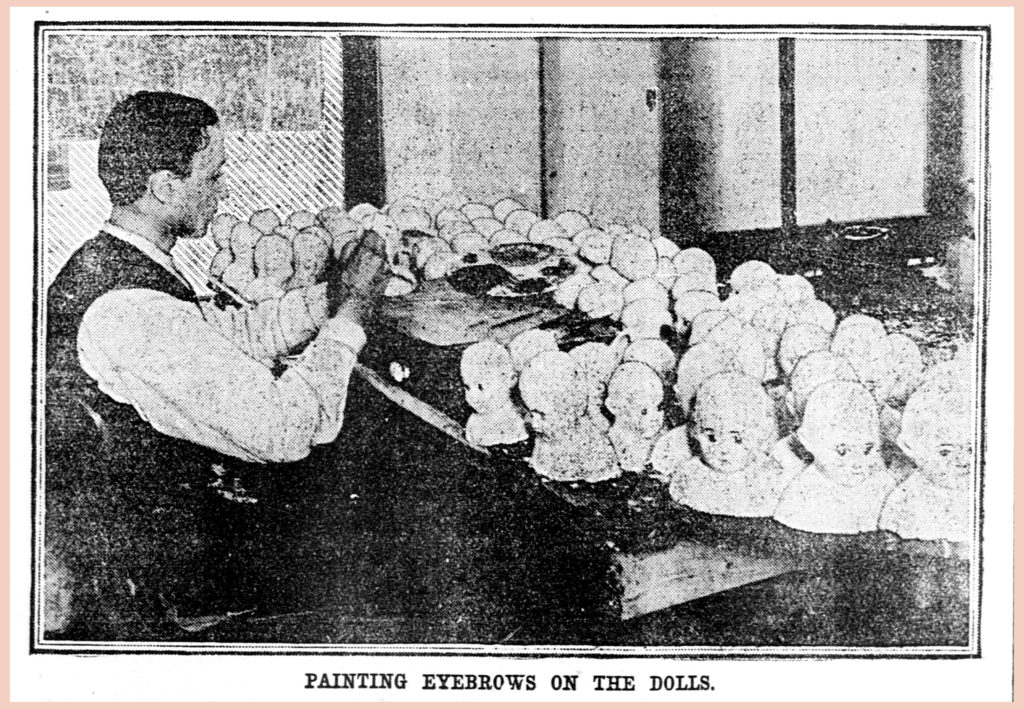

- photo from 1908 Doll Factory

- newspaper story from 1909 – Sonneberg, Capital City of Toyland

1851 Louis Lindner, American Consul at Sonneberg

The American relationship in the history of Sonneberg has a more publicly announced presence when the U.S. President appointed Louis Linder in 1851 to serve as American Consul at Sonneberg, in the Duchy of Saxe Meininger Hildburghhausen, in Germany. The announcement is one of the earliest known mentions of the German town of Sonneberg in American newspapers.

- The Republic. Washington, DC; March 10, 1851.

- The National Era. Washington, DC; March 13, 1851, Page 42

1856 Toys from Sonneberg

The toymaking history of Sonneberg begins to appear in American newspapers mid century 1800s. In Baltimore a store owner advertised a new stock of toys and dolls purchased from Nuremberg and Sonneberg, Germany. (Baltimore Wecker; Baltimore, Maryland; January 26, 1856.) The ad appeared in a German American newspaper. In other newspaper issues of the same paper he continues to announce his stock of toys from Sonneberg.

1860

In 1860 the Gazette includes an article (from the Art Journal) that tells its readers that the best German children’s toys come from Sonneberg in Saxe Meininnen. The writer names Adolph Fleishmann as the principal manufacturer. The Duke set up schools to teach the the trade.

Supposedly a factory focused on papier-mache and wood carving lay in the secret improvement in the history of Sonneberg toy making. Having a well made model in clay or wax allowed less skilled workers such as children to produce a doll. The lightness of the papier mach allowed them to introduce simple machinery for movement. These help lower the cost of producing the toys.

Return to Table of Contents

A Decade of War

The next decade impacted Sonneberg’s trade with the outside world. The three wars from the Danish War of 1862, the Austro Prussian War of 1866, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-17, and even the American Civil War of 1861-1865 slowed down demand for toys and increased tariffs.

As wars ended and trade began to open especially between Germany’s toy industry and the U.S., newspapers throughout the United States began telling Americans the story of the city of Sonneberg, the home of the dollmakers. These are more fun and interesting to read from the perspective of the writers and readers of the year they appeared in print.

NOTE: The following sections of this post are taken straight from the historical newspaper article. As you read keep this in mind. Enjoy.

1875 History of Sonneberg – “Home of the Dolls”

(as found in the The New York Herald. New York, New York; January 2, 1875)

Frankfort, December 8, 1874

“How many thousands of child-hearts are just at this good old season of Christmas made happy in the possession of the annual gifts from Santa Clause of dolls and Noah’s arks, of lead soldiers and dancing figures and all the rest of the world of toys. I wonder if all the children know where Santa Claus procures the many beautiful things he brings them; If the girls know how and where the wonderful speaking, crying and smiling dolls are made? Of course, they have all heard of Nuremberg, and Nuremberg is generally styled the big toy town; but it provides the old saint principally with the cheaper kinds of toys now.

Just on the borders of the Thuringian forest lies the pretty little town of Sonneberg, and it is about this place I intend to write to-day; for here it is that the most beautiful dolls and children’s toys are made at the present time in Germany. It is a wonderfully interesting little town. I visited it in August last on the occasion of a Luther festival held there, an account of which was published in the Herald at the time.

Varieties of Children’s Toys

The great display of toys and Christmas books already exhibited in the windows of the German stores reminds me that I have not much time to lose in sending my letter, if it shall be read a the proper time. Even a description of the toys thus exhibited would be interesting, for some are quite peculiar and instructive. One is pleasantly surprised at the very peaceable character of the toys which we find in South Germany when we remember the whole German, French, and Russian armies that occupied the windows of the Berlin toy stores some years ago, and to a great extent even now.

It has been well said that each nation has a distinctive character about its toys. Well, Prussian toys are essentially military; the children are early provided with big boxes full of calvary and infantry and all the other branches of the army; they are permitted to fight mimic battles and to beleaguer cities, and papa and mamma fondly hope that in time a new Moltke may go forth from their home.

This year the Austrian children are provided, over and above the usual toys, with a very useful North Pole toy, which is set up with some trouble and then represents the adventures of Messrs. payer and Weyprecht on their last interesting expedition to the mysterious North. The ship, the bears, the icebergs, the sailors and even the principal figures seem very old friends to me. Three or four years ago the same toy represented the Germany Koldwey expedition to the Pole.

Thus we see that even the events of the day have an influence in shaping the character of children’s toys. A month after the attempt on Bismarck’s life, made at Kissingen, an enterprising toy maker had manufactured, in that soft gutta percha mixture material of which hideous faces and lizards and frogs are made, the heads of Bismarck and Kullmann, and they may be purchased still for very good Prussian children.

A Daughter of Nuremberg

Well, I must tell you something about Sonneberg and how the toys are made. The Germans call the little town a daughter of the ancient city of Nuremberg, who many years ago was married to the Thuringian Forest; though she is now almost a matron herself, but is far more beautiful than the old lady on the Pegnitz. Sonneberg is a pretty little city of 20,000 inhabitants, situated at the foot of one of the most southern ranges of the Thuringia hills, from which we can look across a broad, fruitful plain as far as Coburg, who fortress is plainly visible, some fifteen or twenty miles distant.

Sonneberg, besides being beautiful, is a very prosperous little place; it carries on a large trade both with England and the United States. The American Consul there is Mr. Winser, in former years a member of the New York press, a pleasant gentleman and a worthy representative, to whom I am indepted for many kindnesses received as your correspondent. I was the first American newspaper correspondent, Mr. Winser told me, who since his residence there and in Coburg had ever invaded the home of the dolls. Through him I was fortunate in securing introduction to the principal toy and doll manufacturers of Sonneberg, the Fleischmanns, the Dressels and the rest. I was very fortunate, too, in making the acquaintance of a retired toy manufacturer, Adolf Fleischmann, who furnished me with some very interesting chapters of Sonneberg toy history from a work in which he is at present engaged.

The Origin of the Sonneber Toy Industry

The Sonneberg toy industry, which arose in the southwestern part of the Thuringian Forest, belonging to the duch of Saxe-Meiningen, dates from the thirteenth century. At first the articles manufactured were of the very rudest description, wooden shingles, staffs, jugs, plates, & co., which were carved by the inhabitants of the mountain villages, wood cutters and charcoal burners, who thus made use of their leisure time. Some of these poor mountaineers then gathered together these wares, and heavily loaded, wandered with them into Franconia, where they disposed of them and returned to the mountains, with meal, wool, cloth or whatever else they wanted for themselves or their neighbors. It was a dangerous life for the poor fellows, for highway robbers were very plentiful, and many a poor toy dealer was robbed of all he possessed and sometimes even murdered.

In the following century, however, a great improvement took place in the condition of the dwellers of Thuringia. A highway from Augsburg and to Leipsic and Dresden was made through the forest; thenceforward caravans of Augsburg and Nuremberg traders passed along the route, and in returning purchased the manufactured wares from the villages. Then the merchants brought to the mountaineers better models from the Berchtesgaden toy makers, taught them how to paint their manufactures and to improve them so that they could be exported as the wares of Berchtesgaden of Nuremberg. This was the commencement of the Thuringian toy industry.

Then some of the more enterprising toy makers commenced business as merchants on their own account. Sonneberg, then a little palce of but 700 inhabitants, became the recognized centre of the trade, and has remained so up to the present time. From 1710 to 1740 Sonneberg merchants established branches in St. Petersburg, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Christiana, Lubeck, London, Moscow, Archangel and Astrakan.

The Good Old Times – Marble Making

A very different business was that of the old Sonnebergers from that of the modern people. Toys were not purchased in such quantities in those days; people were neither so cultivated nor so rich, and doubtless the children had to be satisfied with the simplest and rudest things. But the Sonnebergers had also other business to attend to. They supplied the armies of Europe with flints; they manufactured and sold whetstones, slates and slate pencils; they bgan to manufacture marbles, and glass and iron manufactories were established in the beautiful wooded valleys.

Salzburg Protestant exiles first introduced the manufacture of marbles into Thuringia. They are made in the same way now as then and form a large article of Sonneberg export. You may find half a dozen marble mills in the valley leading from Sonneberg to Judenbach. Children and grown up persons first break the hard limestones into small square pieces, which are afterward ground round in the so-called marble mills. It is estimated that 50,000,000 marbles are manufactured annually, polished and colored and sent from Sonneberg to all parts of the world, and of late years besides marbles of stone are those made of glass, porcelain and other materials. The glass blowing establishments of the valleys near Sonneberg were first founded by Bohemian emigrants who were attracted to Thuringia by the gold washings which were carried on some centuries ago in the mountain valleys.

A Child’s Paradise

Sonneberg exports, as I said, very different articles now from what it formerly did. Perhaps no better idea can be given of the character of the Sonneberg industries than by visiting one of the great showrooms of the place, either that of Messrs. Fleischmann or of Otto & Cuno Dressel. These showrooms are something wonderful in their way, being, in fact, international expositions, we may say, of children’s toys, in at least fifteen thousand varieties. They are paradises where children would go into ecstasies over the wonderful and beautiful things exhibited.

Where to begin in my description is difficult. There are toy men of all races, zones and ages, from little Savoyard up to Prince Bismarck and the Kaiser William of Germany, in wood, porcelain, papier-mache and terra cotta. There are Russians and Poles, Germans and French, tourist Englishmen and Brahmin priests living far more peaceably together on the long shelves than they generally do in the big world. There sits an old grandmamma in her easy chair, and next to her Moses lies as comfortably as possible in the bulrushes; there are pretty winged angels alongside of exaggerated Frenchmen and Alpine hunters; there is Britannia trying to rule the waves, and Germania watching the Rhine, and close by a small bust of Horace Greeley, finely executed in terra cotta.

Then there are figures of dogs and monkeys, drummer boys, jumping jacks, clowns, little ladies at miniature pianos, playing a Strauss waltz or “God Save the Queen;” boys on wooden horses, peasants from Thuringia and Bavaria, the Marquis of Lorne and his princess wife, jugglers and mountebanks, and “maidens, all forlon, a milking the cow with the crumpled horn,” all in various materials, and all very beautifully executed.

Menageries – Dolls – The Beautiful Doll Baby

There are a thousand other things that attract one’s attention. Some are exceedingly quaint. there are long rows of good old Santa Clauses, warmly clad in fur and covered with boar frost, ready to go out at Christmas time with their sacks filled with toys and dolls and sweets. There are the mangers of Bethlehem, with little wooden figures of wise men and shepherds and sheep and the infant Jesus in the manger, in dangerous proximity to the cows. Chicken groups of the quaintest character – two have just escaped from the shell, and stare at each other with mutual admiration and surprise.

There are cats that squall, dogs that bark and horses that whinny, and cows that give milk, provided it be previously supplied through a hole in the back; elephants with trunks that suck up water and spirt it out again in a very natural manner, and birds that sit in delightfully green trees and chirp away until they get short of breath. In short, there is everything that a child ever heard of or could wish for, a thousand objects, the mere enumeration of which would take up two columns of the HERALD.

There are the many toy musical instruments which boys generally delight to torment older people with – flutes and fiddles, fifes and trumpets, drums and tiny pianos, and again needle guns, swords, pistols and cannon enough to supply the German army, Landstorm and all. And dolls! They are there by the thousand; of all sizes and prices, plebeian and noble; some of wood, some of porcelain, some of papier-mache, some of wax; some lying a hundred in a row; others beautifully dressed in silks and furs and bonnets, and sleeping quietly in their doll beds or in beautifuly padded drawers; some sleeping with their eyes closed and some with them open, and some capable of crying mamma or papa when occasion requires.

There was one big doll, I remember, just as big as a four-year-old girl, and nearly as beautiful as some young ladies I know, and it seemed as if it only needed a spark of life breathed into the body to make it speak. I was shown one doll in a beautiful crib, and the manufacturer told me that when it was first finished his wife cried over it and took it and placed it in her own bed and would not give it up for some days, so beautiful and lifelike was it. And now the manufacturer refuses to sell it, because he says, his wife loves it so much and if he took it away he thinks the poor woman’s heart would break. And believe me I am not exaggerating or inventing doll stories, “at all at al.”

How the Dolls Are Born

A visit to a Sonneberg doll manufactory is an exceedingly pleasant and surprising affair. I visited one manufactory where eight persons were employed, besides 150 others who do work at their own homes. The manager informed me that on his trade list he had 695 sorts of dolls, each sort having again six varieties, so we come to the fact of the existence of over 5,000 varieties of dolls.

There are wooden dolls, pot-faced dolls, papier mache dolls, wax dolls, in the making of which are engaged not only the modellers, wax varnishers, & c., but hundreds of children and girls to make boots, dresses, to curl the hair and other important operations on these fearfully and wonderfully made creatures. The dolls with wooden heads and wooden limbs and porcelain heads are the lowest germs of the Sonneberg doll. The heads are imported, but the movable limbs and bodies are cut, carved and put together by the dwellers of the mountains, many of whom follow other occupations.

Thus, in Judenbach, I saw whole families, old and young, male and female, engaged in the interesting occupation of making wooden dolls. The smallest children would have some simple operation to do, such as cutting or sawing the wood into the proper length, an older child would be able to cut out the limbs in the rough, the older members would do the finer work and fix all the anatomical parts together.

When the children are sent out to guard the cows or the sheep they take wood with them and simple knife and return home at night with quite a stock of legs and arms. The curious Papagenos of the Thuringian forest, the bird catchers, are likewise armed with a knife and a peculiar little piece of wood affixed in front of them, and carve the limbs or other pieces of toys, when they have set their snares and are yet waiting for the little feathered victims.

The Wax Doll Manufacture

To make a real wax doll or one of papier-mache is quite a long process. First of all the limbs have to be made. The legs, either of pot or cotton, have to be filled out with moss and sawdust, and the same process is gone through with the body and arms, the task being entrusted to a number of young women. The head is more diffiuclt to make. First comes the moulding, from a kind of whity-brown paste, which when hard is almost indestructible. The head is moulded in two halves, the back and the front, and then the two parts are joined together with the same sort of paste. The heads are made by the thousand, of all shapes and sizes, and left for the moment unpolished and sickly looking.

Then these frame pasteboard heads are carried to the wax room, where they are passed through some severe ordeals. The papier-mache model heads are dipped into boiling wax and thus have the appearance of real wax dolls. But the genuine article, the real dolls of wax, are made thus: – The boiling wax is poured into a plaster mould; it adheres to the sides as it becomes cold, and when the mould is taken apart there is the beautiful wax head, but simple a shell, and of course very weak. The head is cast complete, and only a small opening is left in the crown of the head.

Then a workman takes the wax shell and very carefully lines it throughout with a kind of soft paste about the thickness of cardboard, which soon hardens and gives the head its strength and durability. After this process the head is placed over a hot furnace, the wax is permitted to melt to a very slight degree, whereupon it is dusted with powder made of potato meal and alabaster, to give it a delicate nesh tint. In another room the head is provided with a pair of eyes, and it is no easy thing for the workman to select two exactly alike.

Sometimes, as the children know, dolls squint, and this proves that the workman who put them in was not very careful in his work. Another very skilful workman then receives the head and finishes off the front appearance of the eyes, scooping off all the wax and affixing the lids in a charming manner. Then the eyelashes have to be affixed, and then the little lady has to be provided with teeth, which are put in by a skilful workman one by one.

A still more interesting study is in the hairdressing room of a doll manufactory. All the dolls that come into this room are complete as far as their heads; there they are quite so bald as some old gentlemen of eighty who don’t wear wigs. The hair for these heads is first worked on to a mesh, which fits the doll’s head so nicely that one cannot tell but that it is a natural growth. Then the rough head of hair, with the doll, is sent to the female hairdressers, who are armed with combs and brushes and hot curling tongs, have no small amount of good taste, and would I am sure, make excellent ladies maids.

The hair is made up in the most beautiful manner, in imitation of the very newest fashions; and then when the doll is thus combed and curled it is provided with a delicate little chemisette and placed, with a hundred or more companions, in a huge basket, and transported either to the great storerooms or to the doll milliner, who provides it with clothing and costumes fitting it to appear in the great world.

This will only give you a faint idea of how the wax dolls are made. I have omitted many interesting parts of the process, I am sure, such as how the baby dolls are made to open and shut their eyes and to cry “papa” and “mamma;” but I am also sure that nearly all children have at one time or another looked into these mysteries of doll life, and a description would be superfluous. I must bring this already too long letter to a close before half exhausting the interesting things of Enneberg, trusting only that it may prove interesting to the children world at this pleasant doll-buying season of the year.”

Return to Table of Contents

1876 World Fair in Philadelphia

As a side note, before reading the next news stories, a group of Sonneberg manufacturers attend the World Fair in Philadephia.

1877 US Tariffs in the History of Sonneberg

(As found in the Chicago Daily Tribune. Chicago, Illinois; October 24, 1877)

American Trade with Germany (Washington Special in Boston Globe)

“In further response to the circular recently issued by the Department of State to our diplomatic and consular officers as to the best mode of promoting trade between the United States and their respective countries and districts, the Consul at Sonneberg, Germany, has forwarded a dispatch, in which he says the manufactures of the consular district of Sonneberg are principally toys, chinaware, porcelain, and other fancy articles, the chief market for which has been the United States, but our own manufacturers, protected by the high tariff, have seriously interferred with the export trade of that district.

The Consul, in order to meet the requirements of the trade circular from the Department of State, entered into communication with the leading merchants, manufacturers, and exporters of his district upon the subject under consideration. He has forwarded with his dispatch copies of the answers of these persons, and their unanimous opinion is that one of the requisite conditions for the enlargement of trade between that part of Germany and the United States is a modification of our tariff, for they assert that it cannot be expected that German manufacturers and merchants can take an interest in the extension of American trade in Germany while German manufacturers are shut out from the American market by a prohibitory tariff. The feeling throughout the districts of Sonneberg is one of hostility to the introduction of American goods until a reciprocity of trade by a reduction or our tariff is permissible.”

Side Note

As the author of this blog, the above story might be better understood read together with a continuation story that appeared in 1878 found in The Stark County Democrat. Canton, Ohio; September 12, 1878. The Evening Star. (Washington, DC; March 10, 1879) tells the story of American goods on exhibit in Germany and the resident responses.)

Return to Table of Contents

1886 History of Sonneberg, Toiling Toymakers

A Heidelsberg correspondent of the Philadelphia times writes:

“A half day’s journey from Heidelberg brings the traveler into a region as full of quaint interest and strange sights as any in Germany, the land of toys, the Sonneberg district of Thuringian forest. This world apart in the universe of industry is known very well, indeed, to a certain class of Americans, the toy-importers, better than to the importers of any other nation. The American purchasers are the only ones who come to the Thuringian forest to give orders on the spot, “compose” now dolls out of half a dozen different sorts, order toys by the hundred gross, and vanish to return like the swallows at the end of the year.

As long ago as 1876 we Americans bought in this small forest nest toys to the value of nearly half a million dollars, and in 1880 our purchases had increased to nearly a million dollars, and yet how few of us, when we buy a crying doll for a Christmas present, a wolly dog, a noddling donkey, a “farm-yard,” or any of the thousand toys made of wood, papier mache, or wax, think of the strange little world among the Thuringian hills whence our familiar objects come.

Back to the 14th Century

Back at the beginning of the fourteenth century the little town of Sonneberg had won for itself municipal rights and sent large quantities of wooden wares to the Nurnberg jahmarket, had a guild of its own before the close of the century, and continued for more than four hundred years the gradual development of the toy-making branch which has made its productions known in all the civilized countries of the world from Russia, whither Sonneberg send Easter emblems by the thousand gross, to California, where Sonneberg is represented upon every Christmas tree.

Introducing Papier Mache to the Toy Trade

With the opening of our own century came a new era for Sonneberg when a workingman adapted papier mache to the toy trade. Until then it had been used in Paris for ornaments and in the monastries for figures of the saints. Henceforward it was to take up its abode in the nursery and play-room. This invention revolutionized the trade of Sonneberg. Anyone could do the work required by the new material, whereas the use of the materials before employed had required skill and therefore an apprenticeship.

By degrees the whole population, from the decrepit great grandfather to the tiny primary school child was pressed into the service, and to-day the only skilled workmen are those who turn or carve legs for toy animals or the heads of jumping-jacks, and the carpenters who build tiny wooden stables, theaters, kitchens, shops, etc, such as the children of our wealthier American families delight in.

Return to Table of Contents

Introducing the Crying Doll

As years went by the factory system began to creep into Sonneberg as everywhere else. The first factory met with a popular demonstration of so vigorous a character in the revolutionary year 1848 that the proprietor was obliged to abandon his enterprise, but presently the crying doll was introduced, and from that moment the battle against the factory system was lost. The crying doll became the staple production of Sonneberg, and its production employs almost as many workers as that of all other toys taken together.

Life Among Ingenious Artisans of the Thuringian Forest

These are the two great changes five centuries have wrought in the toy dynasty of Sonneberg, the use of papier mache and the introduction of crying dolls, and there is small likelihood of other important changes in the near future. The merchants are said to have no love for their business whatever, the toy manufacturers are conservative beyond belief, and the workingmen have no money with which to experiment. There is no industrial museum in the district, and the manufacturers oppose the foundation of one because each is afraid that the others may appropriate his models.

The Struggle of Competition and Protecting Inventions

The solitary manufacturer who has patented a toy or two and proposed some wholesale improvements of technique is so cordially hated that he employs a private watchman for his establishment, and does not venture out alone at night. Yet within the narrow limits of its methods of production Sonneberg has the most marvelous array of varied toys. Thus there are sample-rooms with 12,000 to 18,000 sample toys, and many a Sonneberg drummer carries in his sample-books 3,000 to 4,000 pictures and photographs of the productions of his firm or firms.

There is a sad side, too, to the diversity; for it is all the product of the workers, of whose poverty no one who has not visited the town can form an adequate idea. Yet these poor workers have no protection for their right to their own inventions, and the only remuneration for their ingenuity consists in the increased number of orders during the weeks or months in which the invention remains a novelty. Nor is there any art or technical school in the district. Every worker must learn as he may and take the consequences.

How the Work and Live

The workers are of two sorts, the factory hands and the “masters,” who work at home with the help of an employe or two, and of their own families. The position of the master varies little from that of the other workmen. The master occupies a cottage and has a potato patch on the steep, stony hillside. But the cottage and potato patch are usually heavily mortgaged, and in order to pay interest and taxes the family usually rent the best rooms and live in the most wretched close-like dens. The quarter of Sonneberg where the workers live is the oldest of the city. After the Russites had destroyed the city the inhabitants are said to have taken refuge in Grunthal, a long gorge under the protection of the castle.

Return to Table of Contents

Living vs Sleeping Quarters

Shut in by steep hillsides the Grunthal, affords scarce room enough for two narrow rows of houses, so that many of them are built directlly into the hillside. The dwelling usually consists of a sleeping and a living room, both low-ceiled and heated winter and summer in order to dry the wares which stand about the stove upon shelves and boards. The living-room, at once kitchen, workshop, and nursery, is usually light. But the sleeping-room is rarely ventilated and still more rarely ventilated. It contains exactly room enough for two or three beds so close together that no one can pass between them. At night the occupant of the furthest must climb over the intervening ones. Here two, three, or four persons occupy each bed.

Cost of Rent

The poverty and crowding are horrible, the want of dwellings increasing as the factory system draws more and more hands to the town. And these pens are expensive, too; the most wretched of them, with but one habitable room, coasts from 30 to 80 marks, and for the usual sleeping and living room together the workingman pays from 80 to 150 marks. The cleanliness of such dwellings may readily be imagined. The week’s sweeping and sweeping and scrubbing is confined to Saturday afternoon, when the wares are packed ready to be taken to the merchants. The sleeping-room rarely shares the benefit of the scrubbing.

The food of these unfortunates consists of potatoes eaten in the morning with a cup of chickory as lunch with bread. For dinner, potatoes with a herring or some fat from the butcher. The poorest of all go without herring and take salt liquor in which it is packed! Meat is seldom eaten. In Grunthal, where the population is the thickest, there are few butchers, and these few find no custom. Down below in the town of Sonneberg itself the butchers live near together and kill much and often. At four o’clock coffee is taken again or the water in which the butcher has boiled sausage, which these unfortunates call sausage soup. This they get for nothing, or almost nothing, and they cut slices of potato into it.

The Seasons of Work

They toy business does not continue unbrokenly throughout the year. From the end of November to the beginning of March almost complete want of work prevails. These winter monthes are terrible. The poor little savings are gone soon after Christmas, and the family must starve along upon the potatoes that have been hoarded or fall into the clutches of the usurer. The first orders that have come in are from the American dealers, who send soon after Christmas, because the staple articles which they order, doll heads or little dolls and other such things, are cheapest then and at the time of the Leipsic Easter fair the Yankee purchasers appear themselves.

The seaon of wholesale export is from July 1 to Oct. 1, when it reaches perhaps seven-fold the height of the winter export. This brief season must be made the most of by the unfortunate workers if the family maintenance for the year is to be earned at all, and their efforts surpass all description. Fancy working month after month eighteen to twenty hours, day in, day out, Sunday and Monday, in such a dwelling, with such food, and working on Friday the whole night through in order to have Saturday’s task ready for delivery!

After the Leipsic autumn fair, when the urgent orders come, and American telegrams for Christmas goods literally chase each other along the cable, every human being who can set at work is pressed into the service of the toy industry. Whole families work all through the night, and the heat and dust and foul air must have been felt to be appreciated, which reign supreme here, where the fire is keep burning day and night to dry the wares, where a dozen human begins crouch in the low-ceiled pen, and at night a cheap petroleum lamp adds its fumes to the whole.

Return to Table of Contents

Effects of Uncleanliness, Bad Food, and Foul Air

The consequences of such a way of living are inevitable. In spite of the pure preset air that pours down from the heights through every lane and byway, these unhappy people are pale and feeble; they stoop and cough, have flat narrow chests, and are small of stature. Such is the race toy-makers in the Thuringian forest.

In the peasant district, but a short distance thence, a hardy race of Thuringians cultivates the soil; but their lean faces, a dry, bloodless skin, betoken the wretched nourishment and overwork. When the children are a few weeks old they are fed with goats’ milk and bread crusts, and when a child cries a rag filled with crumbs and sugar is thrust into it mouth to be sucked, sleeping and waking. The prevailing cause of death is consumption for those who survive the fifteenth year, and the percentage of deaths of children under six months of age is 22.

To make matters worse prices are steadily falling and employers and employes are unanimous in the assertion that since 1873 the prices of the coarser, cheaper sorts of toys have fallen 50 percent. The orders have increased, but only the burden of toil has kept pace with them. Twice as much is produced as of old and scarcely the old remuneration is received.

It is said with the truth that one-half of the world does not know how the other half lives. How little we who buy our children German toys know of the agony which the race for cheapness, the pressure of the world’s competition, the struggle to hold the American market, despite the American tariff, has cost the men and women and little children who make them.”

Newspapers of the 1886 Sonneberg Story

- The Wahpeton Times. Wahpeton, North Dakota; April 22, 1886.

- The Manitowoc Pilot. Manitowoc, Wisconsin; April 8, 1886.

- The Democratic Press. Ravenna, Ohio; April 15, 1886.

- The Asheville Citizen. Asheville, North Carolina. April 17, 1886.

Return to Table of Contents

1893 World Fair in Chicago – a side note

As a side note, before reading the next news stories, a group of Sonneberg manufacturers attend the World Fair in Chicago. The 1893 official catalogue of the German exhibition at the World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago says that nearly half of the toys made in Germany came from Sonneberg. At that time among the 70 odd export firms in Sonneberg had members familiar with several foreign languages to compete in order to compete in the foreign markets. During the 1850s the Sonneberg doll making developed more with the use of papier-mache and later on, china and wax.

By 1893 Great Britain and her colonies were of equal importance to Sonneberg exports as North America, but South America has fallen away along with France, Austria, and Italy. Even though France, Austria, and Italy had been important consumers back during the 1870s.

The Chicago 1893 catalogue mentions the amount of export from Sonneberg to North America as reported by the American consulate:

- 1885 – $611,214.35

- 1886 – $1,013,636.60

- 1887 – $1,017,363.58

- 1888 – $1,192,034.97

- 1889 – $1,278,619.11

- 1890 – $1,444,231.88

- 1891 – $1,510,866

Return to Table of Contents

1893 History of Sonneberg, City of Dollmakers

“At Sonneberg, which is in the heart of Germany, all the inhabitants are in the business of dollmaking—l2,000 people are all more or less dollmakers—and among them they produce no fewer than 25,000,000 dozen doll babies every year. It is hard to realize what an enormous quantity that is.

After this it sounds odd to say that in Sonneberg it takes 80 persons to make a doll. Yet such is the fact. In Germany labor is subdivided as much as possible, or, in other words, a dollmaker does one little thing from year’s end to year’s end, and thus it comes about that it takes 80 people to make a doll.

Little boys, when they enter the Sonneberg factories, spend a long time in painting nails on dolls’ fingers, for which they are paid about 25 cents a week. Some girls do nothing but fill bodies with chopped hay

or straw. Men pass their lives in painting Dolly’s lashes and brows, and others in putting rouge on her cheeks. So it is with other parts of a doll; each is done by one person. The dolls’ wigs are made by girls at Munich, and their eyes come from a little town only a few miles from Sonneberg and are made by men in their own homes.

Endless are the varieties of dolls. Every Sonneberg manufacturer has about 100 designs. Taste varies, and besides in exporting dolls many things have to be taken into consideration. A wax one cannot be

sent to a very hot or a very cold country. In the former it would melt, in the latter crack. Then if a doll has rubber joints she cannot be sent a long sea voyage, for on arrival at her destination she would be

armless and legless. A sea journey also takes the curl out of Dolly’s hair and the starch out of her clothes, Fashion, more over, is constantly changing. A doll which everybody buys one season is not looked at the next.”

Return to Table of Contents

Newspapers of the 1893 “Sonneberg, City of Dollmakers” Story

This article appeared in several different newspapers. Here is a list of some of the newspapers that shared this story of Sonneberg, the city of Dollmakers:

- THE NEWS; Providence, Rhode Island; September 20, 1893.

- The Pacific Commercial Advertiser; Honolulu, Hawaii; October 14, 1893.

- The Olneyville Tribune; Providence, Rhode Island; November 04, 1893.

- Wood River times; Hailey, Idaho; December 26, 1893.

1900 Collective Exhibit of the Sonneberg Toy Industry

Note: The Official Catalogue Exhibition of the Germany Empire published in 1900 stated that the Sonneberg toy industry employed between 25,000 to 30,000 workers collectively. The yearly production value was 25 million marks.

Return to Table of Contents

1905 Sonneberg “Santa Claus’ Doll Factory”

“Sonneberg, in faraway Germany, it would seem, is the real home of Santa Claus, the magic treasure house where he fills his inexhaustible pack. The town is the in the heart of the Thuringian foreest, where have dwelt so many giants, dwarfs, and fairies. Thirteen thousand persons are busy all through the year in Santa Claus’ chief workshop, even in the sultry days of July, when the thoughts of the rest of the world are far from Christmas. Sonneberg has no other industry than the manufacture of toys, and the entire population is on Santa Claus’ payroll. Of one kind of doll alone Sonneberg makes 2,000,000 a year, and the total Christmas trade brings to the Sonnebergers $6,000,000 annually.

Dolls comprise the largest part of the Christmas output. The maternal instinct is universal among little girls, of whatever nationality.

Over 2,000 women and girls act as dressmakers for the dolls. Some of the toilets are very elaborate and follow the prevailing styles as closely as if they were made for duchesses or reigning queens.”

Return to Table of Contents

1906 Home of Santa Claus

Sonneberg is called the home of Santa Clause. Read the fun story in the Evening Star.

1908 Underwood & Underwood Photo

Return to Table of Contents

1909 History of Sonneberg: CAPITAL CITY OF TOYLAND

“This great city is the capital of Toyland. Few children in the United States, who have so many dolls, toy soldiers, toy engines and toy animals to play with, know where Toyland really is.

There are thousands on thousands of little German children who make these dolls and things for the Christmas trees of other lands. They work all of 12 hours a day. and to make children happier than themselves have a merry Christmas.

Just now the busiest season Toyland ever knew is over. All the dolls are asleep in their crates, and Borne are on the big ocean liners bound for New York and western cities.

Children have often wondered why it is that the toy locomotives they play with are painted in such

bright colors. Locomotives in the United States are not painted that way. But the German locomotives

are.

There are several other smaller towns in Toyland. One of them is Sonneburg, near here, where nothing but dolls is made. First a workman scoops a big lot of sawdust into a vat full of boiling water. He stirs the boiling sawdust for a while, then draws off the water and puts the boiled sawdust into a machine. Here it is ground up fine and mixed with paper and rags.

It’s funny stuff to make a doll out of; don’t you think so? After the pulpy mass is all ground up, he puts it in a second machine, and out at the other end comes bodies, arms and legs of dolls, in different sizes, all separate.

Then little holes are punched in the arms and legs, and young women and girls put wire in the holes and give doll everything except a head.

At another part of the factory the heads are made. First a white past of the same kind of clay that dishes are made of is poured into a mold. When it hardens it is baked in an oven. Each mold is exactly like a little girl’s face.

A man takes little pieces of glass and heats them into the right shape for the doll’s eyes. When the eyes are cool, he paints them blue and brown and gray, just like the eyes of a real baby girl. Then a wig is pasted on top of the doll’s head, and the whole head is fastened on the body.

Girls should not take their dollies out in the rain bareheaded, because the paste will melt and dolly’s hair will come off.

Return to Table of Contents

Sonneberg has one big room where thousands of dolls are dressed. Women and girls have sewing machines and make the dresses just like they would make clothes for a real live baby. Skirts and petticoats, and waist and gowns, and stockings, all are made and dressed by the women. It is a great sight to see them putting clothes on a hundred dolls at once.

These people who make dolls are paid poorly. They work all day and earn from 60 cents to $1.25. Even the men, who make the heavier toys, get only about $12 to $16 a week.

Dolls are made here for Chinese children, and also for the boys and girls of Australia. It takes so long for the dolls to be shipped there that they Toyland people work all the year round at their trade. Chinese children don’t like the American kind of doll, with a goat’s hair wig and pretty dresses.

Soldiers, rigged out in bright uniforms and carrying little popguns, are what the Chinese children want. They make their own dressed dolls of other kinds.

The Teddy bears, Caruso monkeys, polar bears and lions are made in Toyland, too. The finest ones have really furry skins and cost lots of money.

Toyland last year sent over 10,000 tons of toys to the United States from around here, and more than half that much to England.

The largest factory here has 3,000 people working in it. All these have a lot of fairy tales they believe, and they think of the fairy tales and toys they make, and sing songs, and are happy for all their long hours of work.”

- The Spokane Press. Spokane, Washington; November 18, 1909

- The Tacoma Times. Tacoma, Washington; November 9, 1909.

- The Seattle Star. Seattle, Washington; November 9, 1909.

Return to Table of Contents