When learning about the milliners doll or milliner’s model doll, a few basic questions come to mind:

- How did a specific antique doll come to be called a milliners doll?

- What are the characteristics of antique dolls that collectors call “milliners’ dolls”?

- How is the phrase “milliner’s doll” used in literature, newspapers, ads, etc during the time when these dolls were manufactured?

- Are their any earlier images of this type of antique doll connected to a milliner?

Photo Credit: National Gallery of Art

Hopefully by exploring these questions one might gain a better concept of how the term somehow in history got associated with this particular doll.

(Note: This post leaves out the apostrophe sometimes only for SEO reasons, but the writer is aware that it should be milliner’s or milliners’ depending on context.)

Question 1: How did this Antique get the Name Milliner’s Doll?

Some claim that the earliest documentation of the phrase “milliners doll” attached to the papier mache doll head with leather bodies and wooden limbs started with Eleanor St. George description in her 1950 book Old Dolls. Others will say that these dolls could never actually served as models for milliners and therefore they are named incorrectly.

In this newspaper ad from 1957 “milliner’s models” were listed along with antique dolls, kewpies, and foreign dolls using the term in such a natural public way implying that the term was probably in common use at that time to refer to a type of antique doll. This newspaper ad appeared during the time of Eleanor St. George.

Therefore is there an image associated with such a doll with a milliner that dates earlier than Eleanor St. George? Therefore one needs to know how to identify it.

Question 2: How do you Identify an Antique Milliner’s Doll Today?

Eleanor St. George described them in 1950 as having “stiff, unjointed, kid bodies, wooden arms and legs, and papier-mache heads, with a variety of molded hairstyles like those popular from 1820 to 1860.” her book, Old Dolls, includes a photo on page nine of a milliner’s doll with the appollo top knot hairdo typical of the 1820s. According to her they ranged from five to twenty-six inches in height. They usually wore dresses of white net over pink cambric

An antique milliner’s doll will probably have a papier mache doll head on a kid leather stuffed torso. Arms and legs seem longer in proportion than other antique dolls. A short layer of leather covers the joint of the upper leather arm to the lower wooden arm and the upper leather thigh to the lower wooden leg.

The papier mache doll heads with the fancier or higher hairstyles usually date earlier than those with simpler hairstyles. (A museum in Nebraska shares how these dolls receive treatment for conservation. The article shares images of milliner dolls at the museum.)

The milliner’s doll shares similarities to the carved wooden limbed grodnertals or dutch dolls. One must study closely the head and body underneath all of the fashions to better identify the doll.

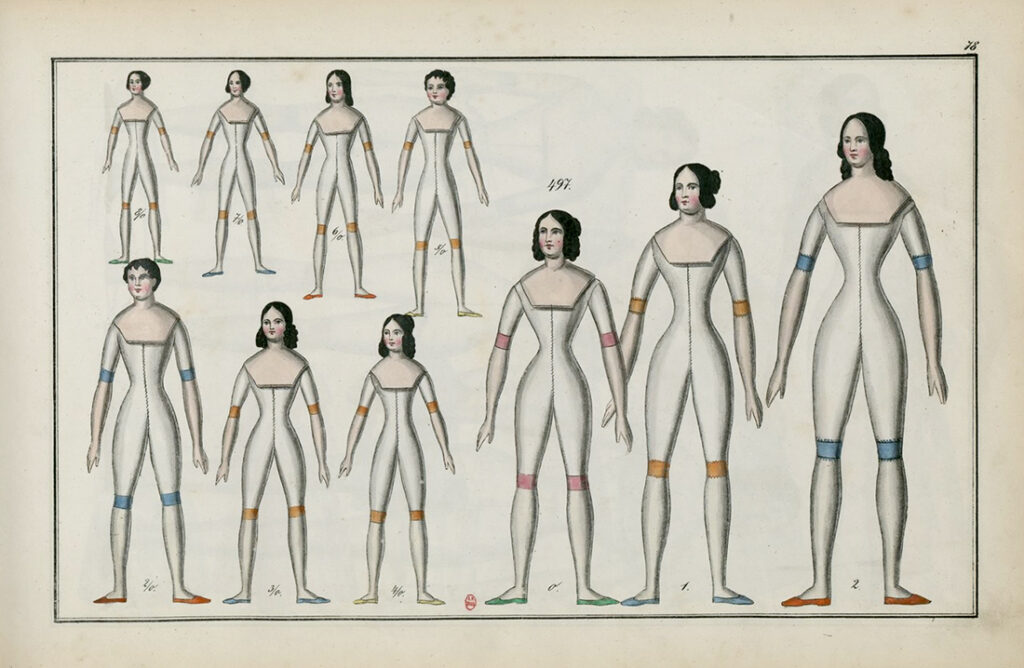

A German toy-maker’s catalogue from around 1820-1830 in the Gallica archives (here) gives a great visual of their structure.

Question 3: How is the Phrase Milliners Doll used in Literature?

The terms “milliners doll” and “milliner’s model” date back centuries. Often times in historic literature characters make reference to milliner’s doll as people fancifully and neatly dressed or as lifeless person or form like a mannequin on display.

Just Dolls

Milliner’s Doll Gifted To Princess Caroline of Brunswick

In 1795 the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal reported that Princess Caroline of Brunswick had received from England two milliner’s dolls dressed in the newest fashion (Saturday 17 January 1795. Page 4). Princess Caroline, from Germany, became Princess of Wales in 1795 which implies the gift may have been in recognition of this event in her life. Another observation finds these two dolls came as a gift from England.

The short line in the newspaper gives no other clues as to the description of these dolls. Here we find the term associated with an object modeling fashions!

The use of the term might imply a milliner and a dressmaker working together to produce such a gift for Princess Caroline, or just a dressmaker. Were they small enough to hold in the hand or large life size models?

For Sale

The London Dispatch on Sunday the 6th of October 1839 had an ad for Teale’s Fashionable Bonnet Shapes at an address of 376, Strand, Lond. The ad advertises the sale of such things as silk bonnets, ladies pelisses and dresses, milliners shapes and models, whalebone, cane, steel busks (used in corsets), wood busks, milliners dolls, and bandboxes. They even list cotton, needles, and tapes, The mention of milliners dolls along with the other items gives an image of a doll small enough to stock several which would be rather different than a lifesize mannequin, unless of course it were a larger warehouse and not a shop.

On Exhibit

One interesting French text from 1871 mentions a” milliner’s doll formerly exhibited on the balcony of the Hôtel-de-Ville” (La Comédie politique,1871-08-06).

Even A Puppet !

A story from 1861 described a man with carrying a puppet on his arm dressed as a man but in the French publication they referred to the puppet as a “milliner’s doll” or in French une poupée de modiste.

Mannequins

The Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser on Friday 5th of November 1841 listed an ad for M. Beckwith selling milliner doll heads.

Another test from Le Temps 1871 uses the phrase “poupees de modiste.” When translated it reads something like “She took my friends for milliner’s dolls and, making them kneel before her, she arranged the ornaments and flowers on them, as if they were mannequins” Sometimes literature used the phrase “milliner’s manikin.” The reference gives the impression that perhaps some milliner’s used a full human like form as a model, not just the head.

A reference from 1890 reads, “My dress seemed to please her, and she asked me to stand up, so that she could see it better. I was turned around as if I were a milliner’s model” (Thirty Years of My Life on Three Continents by Edwin De Leon).

A Dutch Doll, Too

In 1859 in a fictional tale by Albert Smith a character happens upon milliner’s shop window where they see a dutch doll dressed in fancy attire beside fashion plates of the latest styles. So here we see an actual milliner using a small wooden doll to show off fashions but the author identifies it as a dutch doll. (Now we should not assume the use of the word “dutch doll” rules out the idea of the German doll with kid leather bodies, wooden arms, and papier mache heads.)

Milliners Doll Meaning

Implying Neatly Dressed Apparel

Louisa Tuthill wrote in 1848 The Young Lady’s Home giving one a rather good idea of the fashion associated with the term “milliner’s doll.” “…her dress is always scrupulously neat; but if it does not fit with the trim precision of a milliner’s doll, she would be satisfied. She would not willingly offend the eye of good taste in the choice of colors; she would prefer being in the fashion to being out of it.”

In 1866 in “The Extracts from the Journals and Correspondence of Miss Berry” one finds the phrase referencing the neatness of dressed nativity figures. “These are representations of the Nativity of our Saviour, the adoration of the Magi, &c., &c., by little figures about eight inches high, made of terra cotta coloured to the life, and dressed more neatly than I ever saw a milliner’s model.”

Milliners Doll: an Insult

Let’s go back to the 18th century to the year 1790. Elizabeth Hervey wrote a novel called LOUISA. In the book she narrated a scene and conversation where a charactered suffered the insult ” a little painted puppet, a milliner’s doll.”

Implying Weakness

A frivolous or empty nature sometimes defined the term milliner’s doll. Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1833 carried a story where a writer referenced the showiness of the milliner’s doll dress (“tawdry and flimsy dress of a milliner’s doll”). The expression in context implied a superficial nature. The Southern Christian Advocate in 1846 encourages fathers, “let him teach his daughters that they are not dolls or milliner girls, but that they are the future makers or marrers of this beautiful republic.”

Refinement

In 1828 Mary Russel Mitford used the term “milliner’s doll” to set the scene where sisters dress fancifully. “Hetta in a flutter of gauze and ribbons, pink and green, and yellow and blue, looking like a parrot tulip, or a milliner’s doll; or a picture of the fashions in the Lady’s Magazine, or like any thing under the sun but an English country girl.”

The Illustrated London News carried an article in 1851 that describes a display of dolls by Madame Montanari. The reporter wrote, “There are dolls in every stage of doll life-baby dolls, lady and gentleman dolls, and dolls of no particular age, but combining the artless smile of early dollhood with the finished toilet of a milliner’s model.”

Lifelessness

The concept of the mannequin leads some writers to associate the term with lifelessness. In 1861 a text reads, “If you want to have a milliner’s doll to listen to you, go to the doctor’s, and borrow one of his daughters; they have pretty red lips, and never speak a word” (Joseph in the Snow and The Clockmaker by Auerbach).

A rather gloomy image of lifelessness appears in an 1882 French publication. Translated the text reads, ” “On the evidence table, mounted on a stand, like a milliner’s doll, the skull of the late Perrot.”

Question 4: Are there Images of the Doll Connected to a Milliner?

Above I have shared two images found during the research of milliner’s with head mannequins from the 19th century. But the search continued trying to find the typical milliner’s doll associated with the word or in context of a milliner or their shop. The HathiTrust website has one from 1902.

1901 Du Barry Theatre Production

A bit of interesting theatre history from 1901 reveals a direct connection to one of these wooden armed dolls to the term “milliner’s doll.” The reference appears in the book, Mrs. Leslie Carter in David Belasco’s Du Barry, published in 1902. The story of this theatre production leads to better insight in how the term might have stuck.

Research Behind the Items on Stage

In 1901 Leslie Carter portrayed the character of Du Barry in a theatre production by David Belasco. The book describes how they studied the French history, the culture, the social and political conditions to prepare for this production. The book claims they studied the furniture, dresses, instruments, and more in order to set the scenes of the stage. They even went so far as to secure items that had actually belong to Mme. Du Barry!

Du Barry, former Milliner

Black and white photographs, not illustrations, appear on the pages of the book showing many objects it claims had once actually belonged to Du Barry or were replicas. The book does not explain the photo of the milliner’s doll shown on page 13. One must make assumptions.

Inspecting the Milliners Doll in the Photo

In closer inspection of the doll one can see the form of long wooden arms with hands very similar to what many today would call a milliner’s model doll. You might make out the carved individual fingers and a long neck. One cannot see the doll’s feet and she wears a wig.

If perhaps the doll in the photo does not imitate the dolls of Du Barry’s time, it may have come from a near time period. The mystery continues, but it’s date in time could have played into the influence of Eleanor St. George’s use of the term in the 1950s.

The Great Doll of France

In his book, The Story of Du Barry, James L. Ford (1902) describes the story of the Great Doll of France, dressed in the latest styles, which France sent to every court of Europe teaching them how to dress properly. Even people in Venice expected the doll to arrive back in 1788!

“At the beginning of every season, there is exhibited at Venice, says he, in a street named La Mercerie, a female figure in high dress, called the Doll of France; but is the model by which the women are to dress themselves during that season, and any extravagance is elegant, provided it be authorised by this original. The Venetian ladies are not less fond of change and variety than those of France. Tailors and milliners, and traffickers in modes, take advantage of this taste; and if France does not furnish fashions in sufficient variety, there are working people at Venice who have changes of dress for the DOLL.”

Walker’s Hibernian Magazine or Compendium of Entertaining Knowledge

The Theory Behind the Doll on Stage

Ford theorized that Du Barry could have worked in such a milliner’s shop that helped dress this Great Doll of France. Thus another possibility of why a fancifully dressed doll appears among the objects used on the set of the theatre production. Ford’s book includes the same photo as shown in Leslie Carter’s book.

One sees the same reference to the fashions of the doll of France at La Mercerie in the 1894 French publication L’Italie d’hier : Notes de Voyages by Edmond de Goncourt.

Terminology: Fashion Plate or Fashion Engraving

Many times understanding may get lost in translation. Henry-René d’Allemagne (1863-1950) published a book in 1900, “Musée rétrospectif de la classe 100 : jouets à l’exposition universelle internationale de 1900, à Paris : Rapport.” In his book he describes “poupées comme de gravures de modes” or dolls used as fashion plates or engravings better translated as “fashion dolls.” He explains (translated), “The idea of using these small mannequins as sample cards has been taken up in our days by the majority of manufacturers who deal with women’s clothing. These reduced models have the advantage of taking up less space in the display cases and of representing a great saving in the costs of establishment.”

Allegmagne mentions M. Natalis Rondot report of the exhibition in 1849 that (translated) “Parisian workers have no rivals for the clothing of the doll; they know, with marvelous agility and skill, how to take advantage of the smallest pieces of fabric to create an outfit.”

Conclusions about the Milliners Doll

With limited research one might theorize the the popular Du Barry theatre production and Carter’s book possibly impacted a certain group of society in New York that may have carried forward through the years sticking the term “milliner’s doll” with the type of doll in the production.

Curiosities still linger regarding the milliner’s dolls gifted to Princess Caroline in 1795. What did they look like? Do the royal collections of England or Germany hold them in archives anywhere? Would they probably look more like the typical Georgian or Queen Anne type dolls as we know them today?

One can conclude, though, that a milliner’s doll may have been any type of doll of the time small or life size to model fashions either by the milliner or the dressmaker.